THE HISTORICAL KISSI PENNY (‘Money with a Soul’)

PREPARED BY: (Dr.) PAUL FALLAH NABIEU

BACKGROUND

Since the pre-colonial era, different means of payment were adopted by many cultures but for uniformity, the term “money” was agreed upon.

The term "Primitive Money" was the first name. This was later followed by "Precoinage” currencies (before the development of coins) but "Natural Money" (Uncoined forms of money) formed a much wider acceptance. It’s most important and long-lasting representative was the cowry currency, which circulated in many countries parallel to coins. In some places, cowry shells were even a fixed denomination within the currency system. To pay tribute to the diversity of uncoined forms of money, the Money Museum compiles these means of payment under the term "Traditional Money." Such currencies were developed in virtually all cultures. Notable among such traditional money was the kissi penny which we shall talk about in this article.

The Kissi Penny, "bush money" or "money with a soul" as it has been called, is a unique contribution to the world of numismatics. At the end of the 19th century, this unusual iron currency was produced in the Kissi region of Sierra Leone which is part of the Mano River Union of the west coast of Africa. This region has used iron as a trading good and standard of value for a long time. Portuguese records indicated that sailing voyages in the early sixteenth century carried iron bars among the trade good going farther north. Because these rods were made by the Kissi people, the Europeans used to call them Kissi pennies. They regarded it as a curious form of primitive money, and as a result many were collected and deposited in museums. They continue to be sold on art and curio markets, as well as among numismatists to the present day. This currency was popularly known as E Chilin, Chilindae, Guenze, and Koli. Although it was produced in Sierra Leone, it was circulated widely in the immediate vicinity among Gbandi (Bandi), Gola, Kissi, Kpelle, Toma (Loma), Mandinka, Madingo, Mendes and other people of west Africa (Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea-Conakry) and central Africa.

Production

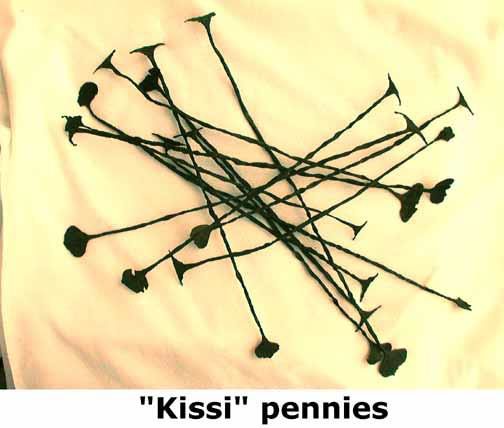

Presumably, this Kissi money was ‘minted’ in the 1880s by "Sumda" (Native Blacksmiths) who used iron smelted from the rich ore in the region. It was made from in the form of long twisted rods, with a "T" on one end (called Niling or "ear"), and a sort of blade, not unlike a hoe on the other end (called Kodo or "foot"). It ranged in length from about 6 to 16 inches (25 to 40 centimeters). The longer ones representing the higher value. Its weight was 35g and diameter of 420.0 mm. The odd shape may have its origin as a means of protection since it was virtually impossible to tamper with the metal content of the piece without noticing it immediately. If this currency would accidentally break, it could no longer circulate and its value could only be restored in a special ceremony performed by the Zoe/shaman the traditional witchdoctor – often the blacksmith – who, for a fee, would rejoin the broken pieces.

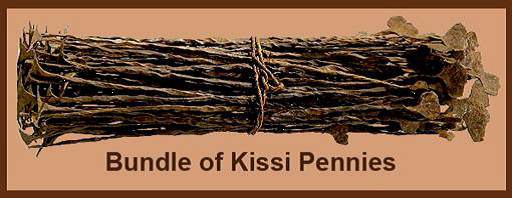

STORAGE

Bundles of the penny was packed in kalandan (parcels intertwined from palm leaves) and hanged on the ceiling of the huts. During the nights, these metals sweat and the water drops on the dusty/mud-covered floor. Sometimes, these drops of water can actually eat into the floor. The first thing strangers look for is the water mark on the unpaved floor and once that is identified, they then go further to raise their heads in search of it in the ceiling. A man’s wealth was known by the amount of sweat that drains from his kalando/kalandan. The more money one has, the deeper the drainage.

Circulation

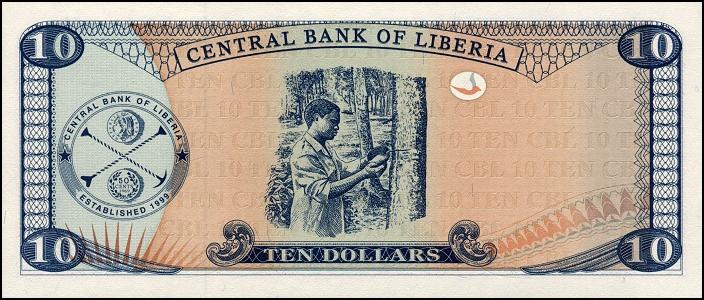

For many decades the Kissi money circulated along with American, British and French paper money. Thanks to the trading and nautical activities of the people of the region, especially the Kru. These pennies circulated widely along the coast of West and Central Africa. Historical records do not note the use of this currency before the last years of the nineteenth century (c. 1880). The French were the first to abolish the use of this money in their colony. The British followed in 1940. In Liberia things went much slower. In 1936, the District Commissioner of Voinjama, Liberia’s Western Province (which borders the French colony of Guinea and the British colony of Sierra Leone) attempted to prohibit the use of the money in payment of the much despised hut tax. Since the North American rubber company did not significantly affect their way of life, the tribal people in the Northwestern part of the country continued to use this traditional money. It was only after emergence of modern employers in the 1960s and the administrative reform of 1964 that the Kissi money was definitely replaced by the official currency of Liberia (US dollar which was introduced since 1944) but continued in use even as late as the 1980s. It is so closely associated with Liberia however that the Central Bank of Liberia has two of these bar-shaped "pennies" crossed on their seal. The seal can be seen fairly well on the L$10 below. (Yellow arrow)

PREPARED BY: (Dr.) PAUL FALLAH NABIEU

BACKGROUND

Since the pre-colonial era, different means of payment were adopted by many cultures but for uniformity, the term “money” was agreed upon.

The term "Primitive Money" was the first name. This was later followed by "Precoinage” currencies (before the development of coins) but "Natural Money" (Uncoined forms of money) formed a much wider acceptance. It’s most important and long-lasting representative was the cowry currency, which circulated in many countries parallel to coins. In some places, cowry shells were even a fixed denomination within the currency system. To pay tribute to the diversity of uncoined forms of money, the Money Museum compiles these means of payment under the term "Traditional Money." Such currencies were developed in virtually all cultures. Notable among such traditional money was the kissi penny which we shall talk about in this article.

The Kissi Penny, "bush money" or "money with a soul" as it has been called, is a unique contribution to the world of numismatics. At the end of the 19th century, this unusual iron currency was produced in the Kissi region of Sierra Leone which is part of the Mano River Union of the west coast of Africa. This region has used iron as a trading good and standard of value for a long time. Portuguese records indicated that sailing voyages in the early sixteenth century carried iron bars among the trade good going farther north. Because these rods were made by the Kissi people, the Europeans used to call them Kissi pennies. They regarded it as a curious form of primitive money, and as a result many were collected and deposited in museums. They continue to be sold on art and curio markets, as well as among numismatists to the present day. This currency was popularly known as E Chilin, Chilindae, Guenze, and Koli. Although it was produced in Sierra Leone, it was circulated widely in the immediate vicinity among Gbandi (Bandi), Gola, Kissi, Kpelle, Toma (Loma), Mandinka, Madingo, Mendes and other people of west Africa (Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea-Conakry) and central Africa.

Production

Presumably, this Kissi money was ‘minted’ in the 1880s by "Sumda" (Native Blacksmiths) who used iron smelted from the rich ore in the region. It was made from in the form of long twisted rods, with a "T" on one end (called Niling or "ear"), and a sort of blade, not unlike a hoe on the other end (called Kodo or "foot"). It ranged in length from about 6 to 16 inches (25 to 40 centimeters). The longer ones representing the higher value. Its weight was 35g and diameter of 420.0 mm. The odd shape may have its origin as a means of protection since it was virtually impossible to tamper with the metal content of the piece without noticing it immediately. If this currency would accidentally break, it could no longer circulate and its value could only be restored in a special ceremony performed by the Zoe/shaman the traditional witchdoctor – often the blacksmith – who, for a fee, would rejoin the broken pieces.

STORAGE

Bundles of the penny was packed in kalandan (parcels intertwined from palm leaves) and hanged on the ceiling of the huts. During the nights, these metals sweat and the water drops on the dusty/mud-covered floor. Sometimes, these drops of water can actually eat into the floor. The first thing strangers look for is the water mark on the unpaved floor and once that is identified, they then go further to raise their heads in search of it in the ceiling. A man’s wealth was known by the amount of sweat that drains from his kalando/kalandan. The more money one has, the deeper the drainage.

Circulation

For many decades the Kissi money circulated along with American, British and French paper money. Thanks to the trading and nautical activities of the people of the region, especially the Kru. These pennies circulated widely along the coast of West and Central Africa. Historical records do not note the use of this currency before the last years of the nineteenth century (c. 1880). The French were the first to abolish the use of this money in their colony. The British followed in 1940. In Liberia things went much slower. In 1936, the District Commissioner of Voinjama, Liberia’s Western Province (which borders the French colony of Guinea and the British colony of Sierra Leone) attempted to prohibit the use of the money in payment of the much despised hut tax. Since the North American rubber company did not significantly affect their way of life, the tribal people in the Northwestern part of the country continued to use this traditional money. It was only after emergence of modern employers in the 1960s and the administrative reform of 1964 that the Kissi money was definitely replaced by the official currency of Liberia (US dollar which was introduced since 1944) but continued in use even as late as the 1980s. It is so closely associated with Liberia however that the Central Bank of Liberia has two of these bar-shaped "pennies" crossed on their seal. The seal can be seen fairly well on the L$10 below. (Yellow arrow)

USES

a. General trade

The Kissi money was a general-purpose currency. In practice its use was quite extensive. A single Kissi penny had only a limited purchasing power. For instance, a bunch of oranges or bananas could be bought for only one or two pennies. This was the reason why they were mostly parked into whole bundles. Several pieces (usually of 20) were twisted or parked together and secured with cotton or leather strips to form Larger ‘denominations’. In the beginning of the 20th century a cow would cost 100 bundles, a virgin bride 200 bundles and a domestic slave for 300 bundles.

b. Cultural uses

After being replaced by Western currencies, the use of Kissi money became virtually limited to ritual ceremonies such as on the occasion of the return of young men and women from the bush schools (Poro and Sande society) or for sacrifices and divination ceremonies. It was also uses for wedding ceremonies. "In earlier times, marriages among the Gbandi were confirmed with a Kissi penny. When part of the bride price is paid, the groom will place a penny on his bride's head and say "THIS IS MY WIFE."

c. Spiritual uses (‘Money with a Soul’)

When a kinsman or kinswoman joins the ancestors in a foreign land or another town, this money was used to bring the soul back home. It was placed on the head side of the grave of the dead a night before the journey. People chosen by the gods are given mythical powers to perform the ceremony. They were specially dresses in a way that they can be easily identified on their mission. Early in the morning of the journey, the penny is picked from the grave and the person neither speaks to anyone, nor looks back, no matter the length of the journey. On arrival home, the money was kept in the corner of the main door of the house of the departed. It is believed that the ghosts reside in these places. They were always fed and worshiped for healing, good luck and farming. They were thought to be the intercessors between the people and the gods.

This currency was also used to decorate the graves of old warriors and for making protective charms. Still many people believe the old money to possess magical powers.

a. General trade

The Kissi money was a general-purpose currency. In practice its use was quite extensive. A single Kissi penny had only a limited purchasing power. For instance, a bunch of oranges or bananas could be bought for only one or two pennies. This was the reason why they were mostly parked into whole bundles. Several pieces (usually of 20) were twisted or parked together and secured with cotton or leather strips to form Larger ‘denominations’. In the beginning of the 20th century a cow would cost 100 bundles, a virgin bride 200 bundles and a domestic slave for 300 bundles.

b. Cultural uses

After being replaced by Western currencies, the use of Kissi money became virtually limited to ritual ceremonies such as on the occasion of the return of young men and women from the bush schools (Poro and Sande society) or for sacrifices and divination ceremonies. It was also uses for wedding ceremonies. "In earlier times, marriages among the Gbandi were confirmed with a Kissi penny. When part of the bride price is paid, the groom will place a penny on his bride's head and say "THIS IS MY WIFE."

c. Spiritual uses (‘Money with a Soul’)

When a kinsman or kinswoman joins the ancestors in a foreign land or another town, this money was used to bring the soul back home. It was placed on the head side of the grave of the dead a night before the journey. People chosen by the gods are given mythical powers to perform the ceremony. They were specially dresses in a way that they can be easily identified on their mission. Early in the morning of the journey, the penny is picked from the grave and the person neither speaks to anyone, nor looks back, no matter the length of the journey. On arrival home, the money was kept in the corner of the main door of the house of the departed. It is believed that the ghosts reside in these places. They were always fed and worshiped for healing, good luck and farming. They were thought to be the intercessors between the people and the gods.

This currency was also used to decorate the graves of old warriors and for making protective charms. Still many people believe the old money to possess magical powers.